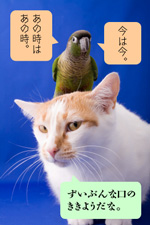

In Toyoko Yamazaki’s “Shiroi Kyotou,” the behavior of the vendor Mr. Nomura towards the Sasaki Store, compared with when the store was thriving, completely changed once the owner died and the store went into decline. Even when confronted with the fact that he used to rub his hands together unctuously, while bowing low when visiting the store, he unconcernedly replies to the effect that “that was then, this is now.”

Those receiving the brunt of such bad manners might point out this character change to the performer of the bad manners: “You’re quite cheeky. When did you get such a big head? Up until now, you were a ‘lackey’ character.” As I have been saying all along, it is unseemly for one’s character to change, except in the context of play.

The perpetrator of said bad manners might excuse himself by saying: “When I was relying on you, I addressed you in a ‘lackey’ style. Now, I no longer rely on you. Therefore, I will no longer address you in a ‘lackey’ style. I just changed my ‘style’ to suit the change of situation.” If there is any logic supporting Nomura’s “unconcerned” attitude it would be this.

When talking to one’s superiors, one uses a certain way of speaking; and when talking to one’s inferiors, one uses another way of speaking—this is exactly the case here. However, when switching between ways of speaking for a superior or inferior, it is quite rare for this to be just a change in style; it also often implies a change of the person (character).

However, the point at which this can be clearly recognized is a thorny issue.

For example, from the point of view of the customer, it is not pleasant to think that the shopkeeper’s low bow is being made not to her, but to her wallet, and is dictated by the situation—this person is my customer now, and is going to pay me money. While it might be overdoing it to speak of “respect for human dignity,” we do tend to expect a bit more than situation and style. However, just because the shopkeeper initially acted humble, it would probably rankle him, even if he wasn’t as bad as Nomura, to be considered an “inferior” by the customer for the rest of his life, even should his customer go bankrupt or he close down his shop to do something else.

Of course, in “Shiroi Kyoto” Nomura is the villain, and is therefore portrayed unsympathetically. However, the principals of Nomura’s behavior are not so far removed from us. There are those who may or may not think that (the romanticized myth that) “in the West, unlike in Japan, the customer and shopkeeper are on an equal footing” is a positive thing. There are also those who might or might not sympathize with the youth who gripes: “I met a customer from my part-time job while jogging, and greeted him without thinking about it. That’s so annoying! Maybe I’ll change my jogging course.”