No matter how heroically you drink booze and sing, if others figure out that you’re doing this in order to be thought of as a “hero,” you are no longer a “hero.” No matter what you say or do, if your intention to prove to others what kind of person you are (a “hero” for example), is detected, your words and actions (your heroic performance) will fail to come across as “heroic” and will not be accepted. However, sometimes this leads to the establishment of a composite character that incorporates that failure. Last time, we ended just as we began talking about failed characters (part 74).

For example, if a man’s intention to act the part of the “heartthrob” becomes self-evident, the character that would be assigned to that failed “heartthrob” is the “poseur.” The “poseur” is the failed character that results when one intends to act like a “heartthrob,” and this intent consequently leads to the failure of the “heartthrob” character.

Another example: when a woman acts cute in an attempt to be an “ojoosama,” and this intention is detected, that woman will be referred to as another type of character ― the “burikko.” The “burikko” is a failed “ojoosama” character.(1)

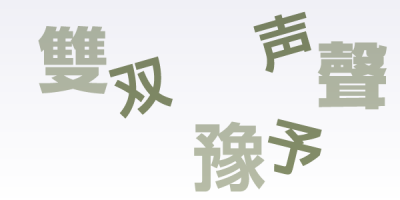

“Burikko” sounds modern enough, but it is in fact what was traditionally called a kamatoto. This name is derived from the disingenuous question: “Does fishpaste (kamaboko) come from fish (toto)?” From days of old, people have been feigning ignorance and detecting feigned ignorance.

The aforementioned “okama” too could be called a type of failed character that results when a man’s intention to perform as a “woman” character is revealed.

Here, my response to our previous problem (see part 73) is unchanged. That is, in talking about “gender” I looked at the “man” and “woman” characters, but not the “okama” character. One could question whether four perspectives is enough, but this question treats “characters” and “verbal characters” as one and the same.

Indeed, the “okama,” as a male, or rather female, failed character is important in considering the topic of “character.” Inasmuch as the “okama’s” manner of speaking is not significantly different from that of the “woman,” it is probably safe to consider the “gender” of this verbal character to be “female.”

Naturally, the speech of the “okama” and the “woman” probably do have some differences. For example, “okama” frequently say the phrase atashitachi okama wa (we okama…) but a “woman” would not. However, we can explain this via common sense ― an okama is an okama; a woman is not. It is not something we need to count as a problem of language (see part 27).

As I said last time, I don’t believe that verbal characters can be rigorously and sufficiently understood with just the perspectives of “class,” “status,” “gender,” and “age.” I think that these perspectives can be used to see just the major features. Granted, “major features” do not include the possibility of a speaker using the phrase “we okama…” when speaking of differences in “okama” and “women.” The point is that I brought up the “four perspectives” as they will serve for the time being.

Additionally, I should mention that in the Japanese-speaking community, not every character that fails becomes a failed character. One cannot assign a specific character to a foreign celebrity who is discovered to have been affecting a “foreigner” character with poor Japanese ability, but who is actually fluent in Japanese and Japanese culture. But maybe there should be a word for that kind of character.

* * *

(1) See Part 25 for more on the “burikko,” “ojousama,” and “kawaiiko” characters.