“Oh, the moon! I’m so happy that we’re going to Shimoda tomorrow. We are going to hold a memorial service on the 49 days after the baby’s death, and mother will buy me a comb. And that’s just the beginning. Take me out to the movies.”

“[Izu Oshima Island] looks so big. You should visit there!”

“Have a seat (okake nasaimashi).”

“Why are you walking so quickly (dooshite annani hayaku oaruki ni narimasu no)?”

These lines from Kawabata Yasunari’s(1) “Izu no Odoriko”(2), are spoken by a dancing girl named Kaoru to the 20 year-old narrator.

“That’s heavier than you think. It’s heavier than your bag.”

In some lines, she comically speaks as if the narrator is her equal, but in general, she speaks from an “inferior” position. So much so that she even hesitates to ask things of the narrator directly:

The dancing girl called to the bird dealer, “Mister! Mister!” asking him to read Mito Koomon Man’yuuki(3) to her. But he soon got up and left. Unable to directly ask me to read the rest of it to her, she repeatedly asked her mother to ask me to read it to her.

[Kawabata Yasunari, Izu no Odoriko 1926]

She had no problem asking the bird dealer to read to her, but not the 20 year-old narrator. Therefore, age is not a problem here. The problem is social standing. The narrator was a student, with a school cap and bag, who the old woman at the tea shop respectfully called “master.” On the other hand, the old lady dismissively referred to Kaoru (although also a customer of the same shop), as “that person,” as she was merely the daughter of a traveling entertainer. Therefore, we can understand, in theory, why Kaoru addresses the narrator as an “inferior,” but it certainly underscores that this story is from a bygone era. She also uses old fashioned language, such as nasaimashi and oaruki ni narimasu no, but even without that we can tell that Kaoru is not a girl born in the modern age. Firstly, she is 14 years old. No matter how important the other person, today’s 14 year-olds would never deploy such an “inferior” character.

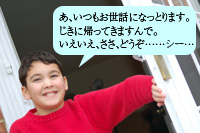

For example, if a 14 year-old today was taking care of his parents’ shop, would he greet customers with a smile, saying: “Ah, thank you for your business. My parents will be back soon. Make yourself at home.” Then suck air through his teeth like an adult. I don’t think there are many 14 year-olds like that, and nor would I expect a 14 year-old to behave that way.

We might expect children to bow deeply and humble themselves in historical dramas, but it’s not seen these days. In this series, I have provisionally called the lowest “status” of person, who is forgiven for speaking brusquely, the “runt” character, but nowadays kids grow out of their “runt” phase much later than they did long ago.

I have already said that the “runt,” which is the lowest “status” is weakly linked with the “baby,” which is the youngest value of “age,” but it seems that the next stage, “youth” is connected to the “runt” too. As I said before (part 63), these days there are a lot “runts” who never speak politely to their parents, like domestic tyrants.

“Isn’t everyone like that?” you ask. Certainly, in the world of manga, Isono Katsuo from Sazaesan and Nobi Nobita from Doraemon are brusque with their parents(4). But Kitaroo from Gegege no Kitaroo(5) and Ikkyuu from Ikkyuu-san(6) use the polite desu/-masu forms with their parents. Hoshi Hyuuma, from Kyojin no Hoshi,(7) speaks brusquely to his parents, but Hanagata Mitsuru, a character from a high-class family, always speaks to his parents politely.

In the Korean language, one always speaks politely to one’s parents. But, the Korean-speaking community is a bit different from Japanese, in that one always speaks politely to a person older than oneself, no matter how horrible that person may be. The whole country is like a giant sports club(8).

* * *

(1) 1899–1972 Japanese novelist. Won the 1968 Nobel Prize for literature.

(2) English title: The Dancing Girl of Izu

(3) Mito Koomon Man’yuuki (The Travels of Mito Koumon) is a famous series of Japanese folktales about the adventures of a retired feudal lord in Edo-period Japan. It is also the basis for a long-running television series.

(4) See part 24 for more on Sazaesan, and parts 9 and 12 for Doraemon.

(5) Manga by Shigeru Mizuki based on Japanese folktales about supernatural creatures or yookai. The main character, Kitaroo, lives with his father, Medama-oyaji, who is a tiny man with a single eyeball for a head.

(6) Ikkyuu-san is an anime series depicting the fictionalized early life of the Zen priest Ikkyuu.

(7) A sports manga and anime series about a young boy’s quest to become a professional baseball player.

(8) At Japanese schools, the sports clubs are notoriously hierarchal. The younger students are always expected to defer to their older peers.