Unlike people in manga, we cannot, barring surgery, actually change our physical appearance for short periods of time. However, as we discussed last time, physical appearance is ambiguous. For example, a person with a sturdy physique could be seen either as an “oaf” or a “reliable boss,” depending on our perception. These characters, “oaf” and “reliable boss,” are from the beginning predicated on perception.

In part 10, I mentioned the expression “ojaru,” which is in use on the Internet. This word (popularized recently by the protagonist of the anime series Ojaru Maru) is used by the “Heian aristocrat” character. However, as I hinted at the end of that essay, “ojaru” is not a word that the Heian aristocracy actually used. As discussed by Satoshi Kinsui in Vaacharu Nihongo Yakuwarigo no Nazo (Virtual Japanese: The Mystery of Role Languages) (Iwanami Shoten Publishers, 2003), “ojaru” is a word that was used by commoners in Kyoto during the Muromachi and Edo eras. The idea that “Heian aristocrats said ojaru” is not reality, but rather a misconception about Heian aristocrats we hold in modern Japanese society.

This is not a foolish misconception. It is because of this misconception that this expression is, after a fashion, still in use in modern Japanese.

A similar phenomenon can be observed in intonation. What do you notice when saying or writing “Ano sa-a, Heian kizoku ga sa-a kotoba o sa-a…” or “Ano yo-o, Heian kizoku ga yo-o kotoba o yo-o…,” as you would say or write “Ano-o, Heian kizoku ga-a kotoba o-o…” (Umm… Heian aristocracy, ya know? Their language, ya know…)? In this intonation, an abrupt rising intonation is added to the “no,” “ga,” and “o” of each part of the sentence—“Ano,” “kizoku ga,” and “kotoba o”—and the final vowel sounds “o,” “a,” and “o” are lengthened while the speaker’s voice trails off (this has various names, but I refer to it as the “returning rising final” intonation).

This intonation has been shown by Kaori Hara, Shiro Kori, and Fumio Inoue, to be associated with unfavorable impressions, such as “childishness,” “lack of intelligence,” “spoiled,” and “bratty.” In a word, it is often seen as the “youth’s way of speaking” which tends to irritate their elders. Kazue Akinaga described in her 1966 essay Seijika no Enzetsucho (Oratorical Styles of Politicians), that this intonation is in fact quite ancient, and was used in Japanese society by adults when debating, and that “upon investigation, it has been found to appear in the speech of the elderly even today.” However, despite such assertions, there is no indication that people’s perception of this intonation as a “style of speaking used by youths” is changing. This is why I say that this is a “youth” character intonation.

Actually, three years ago during a planning meeting for a lecture, I got into a discussion with the organizers, and remember someone saying that “Junichiro Koizumi would never use this intonation, but I suspect that Shinzo Abe had used it somewhere.”

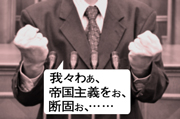

Then I told that person “Your impression might show that Mr. Koizumi has a “boss” character, while Mr. Abe does not. Mr. Indeed Abe is taking quite a beating from his own character,” and oddly enough, Mr. Abe resigned from his position as Prime Minister the next morning.

The fact that characters are predicated on our perceptions also means that they are colored by our various biases. In recording my observations about characters, I hope not to be carried away by such prejudices.