In Fujio Akatsuka’s(1) manga, which I devoured ravenously as a child, each character had a colorful, unique way of speaking. For example, Iyami(2) said things like “Mii wa kanemochi zansu” (“Me am rich zansu(3)”), while Nyarome(4) said “Ore to kekkon shiro nyarome!” (Marry me nyarome!(5)).

Eventually I became an adult, but this does not necessarily mean that I realized manga are nothing more than empty figments.

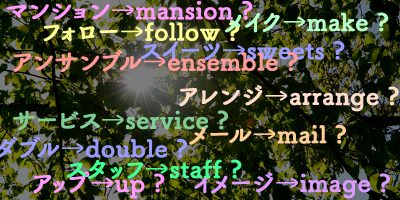

The Internet, in which all of us inevitably spend some fraction of our daily time, is connected to Akatsuka’s world in a number of ways. On the Web, it is already common for people to create various personae or characters with phrases such as “Sessha(6) biriya-do ni itte kita de gozaru” (“We have paid a visit to the billiard hall”) or “Uso da yo pyo-n(7)” (“Just kidding”).

Apparently, the common-sense view is that such expressions are no more than an “aberration in modern parlance,” and should be deliberately ignored as they degrade the “dignity of the Japanese language.” But suppose these turns of phrase contain elements quite capable of both demolishing and vastly evolving our former grammar?

In Japanese grammar, it has traditionally been understood that only sentence-ending particles can appear at the very end of sentences. Nothing is ever added after a sentence-ending particle, other than another sentence-ending particle. For example, one can add the particle yo to the sentence “Ame da” (It’s raining.) to make the exclamation “Ame da yo” (It's raining! [emphatic]). One could further add the particle na to make the sentence “Ame da yo na” (It's raining! [casually emphatic]) but after this no further particles can be added. Or, one can add the particle wa(8) to the sentence “Ame da wa” (It's raining. [feminine]), then further add a terminating ne to create “Ame da wa ne” (It’s raining, isn’t it?).

However, particles such as the pyo-n in “Uso da yo pyo-n.” and pu-n(9) in “Dare ka ne pu-n” (Who’s there?) appear in places where, according to the rules of grammar, they aren’t supposed to――after the terminating yo or ne.

An astronomer who wants to learn about the stars must first observe them with an impartial attitude. The astronomer, observing that the stars failed to appear at the position and time s/he calculated, couldn’t dismiss this by calling it an “aberration in modern stars.”

Similarly, those who wish to study language must observe it objectively. One must resist the urge to talk of “aberrations in modern parlance” and keep an open mind to the language of manga and the Internet in order to find things of interest within them. The appearance of a whole category of words in this unexpected place (after the final terminating particles in sentences) constitutes the discovery of an unforeseen part of speech (the “character-particle” if you will). It forces us to revise our ideas about sentence structure. Furthermore, it forces us to rethink the concept of the sentence itself. This is mildly spectacular.

One can see analogs to the character-particle in Korean and Chinese, but I know of no language other than Japanese that has so freely and actively created character-particles to flesh out its characters. Japanese society is increasingly a society composed of characters. So, let’s have a look at how people in this society live, and sometimes suffer, in their characters.

* * *

(1) 1935–2008. Japanese manga creator, perhaps most famous for Tensai Bakabon.

(2) A character that parodies mass media figures in the manga Osomatsukun.

(3) The English pronoun “me” has been adopted into Japanese, and is sometimes used in place of the Japanese pronoun for “I,” usually for comedic effect. Similarly, “zansu” is a now-obsolete verb that is sometimes used humorously.

(4) A stray cat that appears in the manga Mooretsu Atarou.

(5) In Japanese, the sound of a cat mewing is rendered “nya,” so this phrase could also be translated loosely as “Marry meow!”

(6) Sessha is a formal word for “I”. Sessha is almost invariably used in Japanese film and media by Edo period “samurai” characters, in much the same way “thou,” “thee” etc. are used in English pop media by “medieval” characters.

(7) Pyo-n is one of countless informal sentence-ending particles used in Japanese comics and Internet forums to express character or individuality. The use of such particles in formal writing and speech is generally frowned upon.

(8) Wa is a sentence-ending particle usually used only by women for emphasis, or simply to make their speech sound more feminine.

(9) Another informal sentence-ending particle.