Over the last two parts (Part 22 and Part 23), we looked at Yasushi Inoue’s Shirobamba and its protagonist Kosaku, and got a clear picture of various children.

Here, we must not forget about the character Ranko from Shirobamba. She is a young girl who is a model “ojoosama(1)” character.

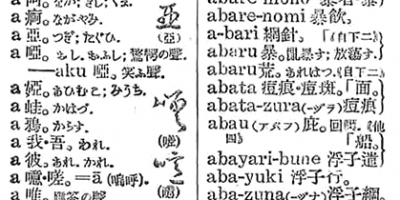

She frequently uses expressions such as “Odamari!” (Silence!) and “Oyame!” (Desist!). These expressions consist of the infinitive form of a verb (“damaru” (to be silent) and “yameru” (to stop or quit) in this example) prefixed with “o” to make a command form; this language is a special pattern used by the “madam” character. In one scene from Shirobamba, Nanae, Kosaku’s strict mother, washes him while using this command form continuously, but Ranko, who is younger than Kosaku, manages phrases like, “Ushiro muki ni natte oaruki!” (Turn around and walk!), “Odamari! Omaesan, nani itterunda. Nanimo wakarimo sen kuse shite!” (Silence! What are you saying? You know nothing!) etc. What else could she be, if not an “ojoosama?” Although one can’t escape the feeling she picked up everything that comes after “omaesan(2)” by listening to adults, she has fully owned these words, unlike, for example, the character Tara-chan from Sazaesan(3), who picks up adult expressions such as “you suru ni” (in short) and shows them off childishly.

Ranko’s talents do not end here. Her use of the word “sa” to prompt others is an “adult” pattern, used in Shirobamba by adults such as the grandfather, grandmother, father, mother and teachers. Despite being a child, Ranko says things like, “Sa, hayaku iinasai!” (Well? Spit it out!) “Sa, Ranko-chan, umi-e iku-wa-yo. Minna irasshaiyo” (Well, Ranko-chan is going to the beach. Everyone, come with me!).

Of course, referring to herself in the third person as “Ranko-chan” is “childish.” The scenes in the book where she rolls up her sleeves and throws stones into the ocean in imitation of Kosaku, and the part where she throws a cake at the ceiling, are also “childish.”

However, there are numerous specimens of Ranko’s adult linguistic patterns: her manner of expressing surprise with falling intonation in the word “a(a)ra” (oh!), as in “Aara, irasshai!” (Oh! Come in.) and “Ara, tobikomeru-no?” (Oh, can you jump in?); her use of “soo”(that’s right) in acknowledgement, when she says, “Soo, sore-wa shiranakatta-wa” (That’s right, I didn’t know that); her use of the command “…shite goran nasai” (try …ing), for instance “Sonnara tobikonde goran nasai” (If that’s how it is, why don’t you try jumping in?).

While a tinge of the “child” still remains in Ranko, her character’s foundation is to some extent “adult,” the “madam” character in particular. She is clearly an “ojoosama” character.

However, her particular character is just one type of “ojoosama.” There is another type of “ojoosama,” as we shall discuss next time. (To be continued.)

* * *

(1) The word “ojoosama” means “princess.” Much like the English word, it is used idiomatically to refer to young women, either endearingly or somewhat judgmentally.

(2) “Omaesan” is a deferential form of the pronoun “you.” It is normally only used by adult speakers toward yonger acquaintance.

(3) Sazaesan is a phenomenally popular comedy manga and anime series created by Machiko Hasegawa. The story follows the everyday life of the titular housewife Sazae and her extended family. Tara-chan is the name of Sazae’s young son. The original comic strip series ran from 1946 to 1974, while the TV animation, which started in 1969, is still being produced today.