Having discussed Shirobamba last time, I would now like to talk about my first “hoo(1)” (wow) experience.

However, to be honest, I don’t remember the exact circumstances under which I said “hoo” for the first time. Here I will talk about the first time I consciously used “hoo.”

It was a very, very long time ago.

I was a third-year student at K. Kindergarten in Tokyo, and we were assigned the task of making a set of karuta(2) cards together.

The person assigned to a had to think of a word that began with that character, such as ari (ant) or akatonbo (dragonfly) and draw a picture of it on construction paper. The same went for i, u, and e(3). I don’t remember whether we had someone for each letter all the way to wa or not, but I was assigned ho.

What word should I pick?

Hoshi (star)? That’s no good. Doing something easy like drawing a star and coloring it gold would be a total waste of my talents.

How about hotaru (firefly)? I rejected this idea too. I hated bugs.

After pondering for some time, I arrived at “hoo.” The same “hoo” that people say under their breath when they’re impressed by something.

How should I depict “hoo” then?

A man is drinking at a bar.

A beautiful woman walks in and murmurs something like, “There is more than meets the eye to the President’s suicide.”

The man’s eyes narrow, glinting. “Hoo (Wow). Tell me the whole story then.”

This is the scene I imagined.

Obviously, this scene is too complex for a kindergartner to draw.

My “hoo” picture was a mess.

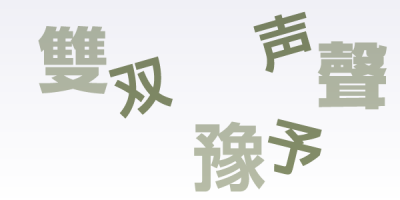

When impressed, children sometimes say “fuun” or “hee.” However, children do not usually say “haa” let alone “hoo.”

It’s not that they don’t understand “haa” and “hoo.” Even children understand that when adults on TV say “haa” or “hoo,” it is because these adults are impressed by something. But children themselves don’t say “haa” and “hoo.”

It’s not because “haa” and “hoo” are harder to pronounce than “fuun” or “hee.” When playing house, children playing the roles of “adults” easily say “Hoo, kyoo wa gochisoo da ne” (Wow! Today’s dinner looks great.). However, they stop using it once their game of house ends.

Children don’t use “haa” or “hoo” because it is not in their nature; that is they know it is not a word their own characters use.

Why did I set out to depict a bar? For just this reason. I knew that “hoo” was not a “child” word, but an “adult” word. So, I had no choice but to draw an “adult.”

* * *

(1) Hoo is a Japanese interjection that indicates the speaker is interested, impressed or mildly surprised. Similar interjections (mentioned later) are “fuun,” “hee,” and “haa.”

(2) Karuta is a Japanese card game in which players try to be the first to snatch the correct card from a large selection of cards. The most common form of this game uses one phonetic character (hiragana or katakana) on each card. Players listen to hints, read by a referee, to determine which card they must grab.

(3) A, i, u, and e are the first four characters in the Japanese syllabary. Wa is the last.